|

On

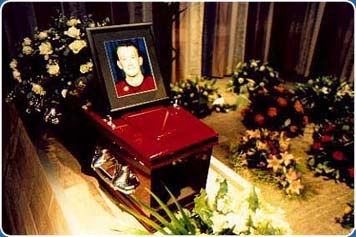

September 30, 1999, Sander was cremated in his home town of

Enschede, The Netherlands. Several friends and colleagues

gave speeches. Here, you can find Eveline's

speech and Richard

Lambert's speech.

Eveline's

speech

I'd

like to start with a big welcome for everybody and thank you

for being here.

That's

one of the strange things for us, as family; to realise now

how many friends Sander had and how many people he knew.

I'm

just his little sister. He was always my big brother, who

was traveling around the world and living in faraway countries.

He would come back to Holland once or twice a year, and he

would take me to the beach, or some other place, to walk and

ask me how I was, and what I had been doing. I have had so

many good conversations with my big brother and he really

helped me out with some good advice more than once.

And

he would tell funny things that happened in his life; in Russia,

in Kazakhstan and in Indonesia.

But

in Holland he never talked so much about his work. He never

boasted about anything. I remember one e-mail of him saying

that he didn't really have any news to tell me, and at the

bottom he wrote "oh yeah, and I shook hands with Habibie."

That was Sander.

He

actually taught me how to windsurf, and how to dance the 'cha-cha-cha':

me standing on his feet and holding on to him tight, and he

would dance with me. I was maybe six and he was fifteen.

As

a child he used to read a lot. He had literally hundreds of

childrens' books, and later he wanted me to read them, too.

He would actually blackmail me, and say: no, you can't have

that cookie until you've read the entire book of 'Pinkeltje'.

I hated him for that.

But

I learned so many things from him. He was my big example,

and that's what he will always be, not only for me. Only now

I realise, that Sander was not just my big brother; he was

many people's friend and colleague, and a very special one.

Also for me: he was not just special for being my own brother.

Hundreds of people have all these good memories of Sander,

and those memories are there to stay forever.

We

have actually laughed our heads off some times in the past

few days, talking about Sander and remembering the way he

was and the things he would do.

When

our father, for example, would make tea for us, Sander would

always take a good look at it first, and often concluded,

when it was too strong, "this is not tea, it looks like coffee".

He used to call this kind of tea 'heart attack tea' ('hartverlammingsthee')

and I always had to laugh about this.

He

lived on tea; since he didn't drink any coffee, he always

drank tea. And when I drink tea, I usually put sugar in it.

"Yak! How can you put sugar in your tea!" he'd say. "That

is disgusting."

Those

few days that he would spend with us were always fantastic

and I'd look forward to them for weeks. And exactly because

of the reason that we spent so little time together, our contact

was always very intense. We would have good conversations

and do fun things every single time we would be together.

That was the great part about my far-away-brother.

Actually

I think there was no better place for him to die than where

he did: at work. Because his work was his life and that is

what he died for.

He

went to East Timor to show the world the truth,... and that

is what he did.

Eveline

C Thoenes

Richard Lambert's speech

I

am here on behalf of Sander's friends and colleagues on the

Financial Times, and of many readers around the world, to

tell you about our pride and respect for him as a journalist,

and our sense of shock and sorrow about what has happened.

And I want to convey our deepest sympathy to his family, and

to Ian.

In

the past week, our office has been flooded with e-mails and

letters.

Some

came from his colleagues and friends. They spoke of his enthusiasm

and charm, of his boundless curiosity, of his generosity and

courage.

That's

my enduring memory of him too. Our first meeting was in Moscow,

when he was still working for the Moscow Times. He cornered

me at a cocktail party, and with energy, determination and

charm told me how - one day - he was going to work for the

Financial Times, more or less whatever I might feel about

the idea.

Some

letters came from the great and good, the people he wrote

about, or whom he came across in his professional career.

They

spoke of his integrity and persistence, and of the respect

they felt for him. They said he had made a difference.

And

some came from people who only knew him through his work,

and who admired and respected him for that.

I

quote from one letter:

"I

never met him, but I feel as though I have lost a personal

friend who kept me in touch with a distant and difficult part

of the world."

Over

the past few days, I have been re-reading what Sander wrote

for the Financial Times in recent months.

Several

things have struck me.

One

is the sheer breadth of his reporting.

In

the last two weeks of his life, he wrote not just about the

horrors of East Timor or the political manoeuvrings in Jakarta.

He also published pieces on the country's banking scandal,

and - as you might expect from the Financial Times - on the

performance of its stock market.

Another

was the quality and sophistication of his analysis. In particular,

I'm thinking of a feature he wrote just a few weeks ago about

the shifting balance of power in the Indonesian military.

A

third striking quality I noticed: his reporting is always

illustrated by the voices of real people. He wasn't satisfied

just to go to the press briefings or to work through the approved

press intermediaries. He wanted to know what people who were

actually on the front line were thinking.

I'll

give you just one example.

At

the end of August, he noted that red and white Indonesian

flags were fluttering across a town in the mountains of East

Timor. But, wrote Sander, these flags should not give the

president hope. "I don't have the option not to fly the flag",

he quotes one farmer as saying. "I'm forced to do it." The

final thing I noticed, subtle but unmistakable, was a growing

sense of frustration and then anger about what was happening

in East Timor. There's the cool analysis, yes. But there's

also something else.

At

the end of a long and powerful feature we published just three

weeks ago, he quoted a rather pompous remark from the New

Zealand foreign minister, a Mr McKinnon.

Then

came the final paragraph.

"Mr

McKinnon forgets what is on the line first of all: the lives

of some 800,000 Timorese, who trusted the United Nations to

bring them not just a ballot, but a future."

Like

everyone here, I suppose, I have spent the last days trying

- and failing - to make sense of what has happened.

Casting

around, I've found three sources of comfort, which I will

share with you.

One

is that Sander loved what he was doing, and he was very good

at it. He had wanted for a long time to work for the Financial

Times, in Indonesia, and he had the satisfaction of knowing

that his work was widely admired.

The

second is that he was not a reckless man. He thought carefully

before he exposed himself to danger.

In

the words of someone who was with him in Dili last week:

"What

he did that day was within the limits of what a reporter has

to do to find out what is really happening."

Third,

and perhaps most important of all, what he was doing mattered.

A lot of what gets published in newspapers is routine information.

But there is more to it than that. Reporters, especially those

who work in difficult and remote parts of the world, give

us the tools which help us to understand complex issues, and

to make judgements on which policymakers must, eventually,

take action.

Finding

out what is really happening is important.

The

conflict in East Timor threatens to change the map of Asia.

There

is growing uncertainty in the region - an uncertainty which

emanates from the towns of Timor and which echoes in Washington,

Tokyo and other Western capitals.

Policies

that affect the lives of millions of people are being influenced

by reports from the streets of Dili.

Sander

reported what he saw. He brought the honourable qualities

of intelligence and objectivity to a place of horror and of

chaos. No journalist, no citizen, could have done more.

|